Calcium is a mineral that most of us have been quite familiar with since childhood thanks to “Got Milk?” commercials and reminders that we need calcium to “build strong bones.” We have more calcium in our body than any other mineral. We’re told to drink milk because it’s full of calcium and helps build strong bones, but do we really understand all the functions of calcium and the various places that it can be found? Today, we’ll explore just that.

As mentioned above, calcium is most certainly essential for maintaining strong bones. When we consume it, our bodies innately know to store it in our bones and teeth to support their structure. In fact, 99% of the calcium that we consume is stored in bones and teeth [1]. Until age 30, our bodies work very hard to store up calcium that we’ll need for healthy bones in our later years. Around that point, our bones reach their peak strength and calcium content and then start to gradually decline in calcium absorption. However, maintaining sufficient calcium intake and participating in bone-strengthening activities such as weight-bearing exercise can prevent significant loss [2]. Bone strength isn’t all calcium is needed for. It helps our body release hormones such as insulin, supports muscle contraction, nerve transmission, cell signal and it helps our blood vessels move throughout our body. If we don’t consume enough calcium, our bodies actually pull calcium from our bones to use for those additional functions [3].

Many individuals don’t consume enough, which increases risk for osteoporosis later in life as well as high blood pressure [4]. According to the National Osteoporosis Foundation, “Osteoporosis (which means porous bones) is a bone disease that occurs when the body loses too much bone, makes too little bone, or both. As a result, bones become weak and may break from a fall or, in serious cases, from sneezing or minor bumps [5].” Additionally, insufficient calcium intake during childhood can result in individuals not reaching their full height potential [6]. Before you reach for a calcium supplement, first try calcium-rich foods. Research has found that calcium supplementation can result in increased risk of cardiovascular disease as well as increased risk of kidney stones. The risk was not found to be true with calcium coming from dietary sources [1].

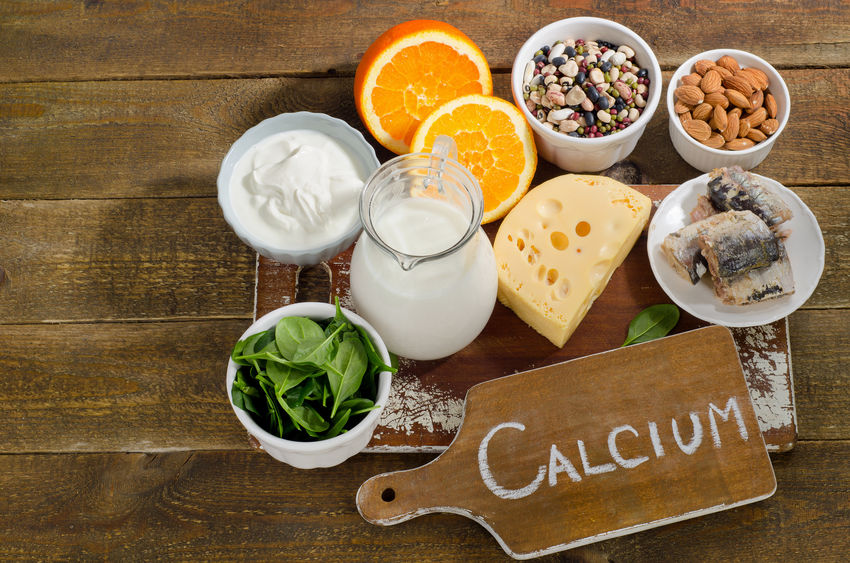

Dairy is probably what initially comes to mind when you think of calcium-rich foods, and you’d be right! Dairy foods provide an excellent source of calcium and several dairy foods also are fortified with vitamin D which increases calcium absorption.

Some examples include [7]:

- Yogurt

- Cheese

- Milk

However, if you follow a vegan diet or have a dairy allergy, there are plenty of ways to get what you need! This list is actually longer than dairy-rich foods [7]:

- Tofu

- Soymilk

- Fortified Orange Juice

- Fortified Cereals

- Sardines and Canned Salmon (with bones)

- Turnip Greens

- Kale

- Chia seeds

It’s important to note that, contrary to vitamin D enhancing calcium absorption, certain foods decrease calcium absorption. Phytic acid and oxalic acid, found naturally in some plants, bind to calcium and can interfere with its absorption. Spinach, collard greens, sweet potatoes, rhubarb, and beans are among the foods with high levels of oxalic acid. Beans, seeds, and nuts are some of the foods high in phytic acid. These foods do contain a host of other nutrients and are very good for you. Rather than omit them, consume them apart from meals with calcium-rich foods.

So how much should you consume? The Cleveland Clinic put it in practical terms and recommends consuming two to four servings of calcium-rich foods per day which is about 1 cup of each food [4]. If you like actual numbers, you can reference this table from the National Institutes of Health with recommended daily allowances [7]:

Age Male Female Pregnant Lactating

0–6 months* 200 mg 200 mg

7–12 months* 260 mg 260 mg

1–3 years 700 mg 700 mg

4–8 years 1,000 mg 1,000 mg

9–13 years 1,300 mg 1,300 mg

14–18 years 1,300 mg 1,300 mg 1,300 mg 1,300 mg

19–50 years 1,000 mg 1,000 mg 1,000 mg 1,000 mg

51–70 years 1,000 mg 1,200 mg

71+ years 1,200 mg 1,200 mg

[1] Thalheimer, J. C. (2016, January). The Calcium Debate – Today’s Dietitian Magazine. Today’s Dietitian. https://www.todaysdietitian.com/newarchives/0116p36.shtml

[2] National Institutes of Health. (n.d.). Office of Dietary Supplements – Calcium. National Institutes of Health. Retrieved May 28, 2021, from https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Calcium-Consumer/#:%7E:text=Bone%20health%20and%20osteoporosis,content%20by%20about%20age%2030.

[3] Antinoro, JD, RD, LDN, CDE, L. (2013, July). Calcium Controversy — Why Dietary Sources Trump Supplements. Today’s Dietitian. https://www.todaysdietitian.com/newarchives/070113p50.shtml

[4] The Cleveland Clinic. (2019a, January 12). Increasing Dietary Calcium. Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/drugs/16297-increasing-calcium-in-your-diet

[5] National Osteoporosis Foundation. (2021b, April 12). What is Osteoporosis and What Causes It? https://www.nof.org/patients/what-is-osteoporosis/

[6] Mayo Clinic Staff. (2020, November 14). Calcium and calcium supplements: Achieving the right balance. Mayo Clinic. https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/nutrition-and-healthy-eating/in-depth/calcium-supplements/art-20047097?reDate=31052021

[7] National Institutes of Health. (n.d.-b). Office of Dietary Supplements – Calcium. Retrieved May 28, 2021, from https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Calcium-HealthProfessional/