The Doctrine of Signatures

Many folks are interested in how plants might have medicinal properties and be useful in various disease states. The idea is that some medicinal plants have been used for centuries and many of our current drugs have their chemical roots in substances isolated from plants.

Last week I wrote about the delivery of my new granddaughter, which appeared to be brought on by eggplant parmesan. Evidence for eggplant includes numerous anecdotal reports; but the pregnancy was “late” and it might just be a coincidence that eggplant immediately preceded delivery.

Identifying which plants have medicinal properties has been a goal of pharmacologists for centuries. At this time, chemicals are isolated from plants and tested in a variety of assays to find chemical structures which produce biological effects. Insofar as plant substances are not patentable, active chemical structures are further modified by pharmaceutical companies to improve their drug properties and profitability. But it was not always so.

Paracelsus (1493-15410 was a 16th century pharmacologist in Basel, Switzerland who proposed many interesting ideas that are still considered important today. One of his ideas was that all drugs are poisonous if the dosage if too high. He endorsed another idea that helped identify plants with medicinal properties: the doctrine of signatures.

Paracelsus (1493-15410 was a 16th century pharmacologist in Basel, Switzerland who proposed many interesting ideas that are still considered important today. One of his ideas was that all drugs are poisonous if the dosage if too high. He endorsed another idea that helped identify plants with medicinal properties: the doctrine of signatures.

Paracelsus was a dominating figure with a high very opinion of himself. He believed that God communicated with him directly. And one of those communications was that plants with medicinal properties would be marked by a sign: looking like the organ that they were meant to treat. Paracelsus would be intrigued by the idea that eggplant might be useful in stimulating labor because an eggplant looks a lot like the uterus, the organ in which babies grow.

You can find easily find support for the Doctrine of Signatures. Some of the facts used to support the Doctrine include:

- if you slice a carrot, the center looks like an eye, and carrots are good for your eyes

- tomatoes are red and have chambers like the heart; tomatoes are good for your heart

- walnuts look like the brain and are good for your brain.

There are also some good reasons to doubt the Doctrine of Signatures. Being “good for” is not the same as being a medicine. There are plants that look like various organs and yet do not provide medicinal benefit. Avocadoes look more like the uterus than do eggplants; why don’t avocadoes stimulate labor? Walnuts may be good for your brain, but they also look a lot like male testicles; are they good for raising testosterone?

A number of drugs DO come from plants – like digoxin for the heart – but the digitalis plant doesn’t look like the heart.

As patients consider botanicals as medicines, they often take comfort in the idea that plants have been used as medicines long before pure drugs were isolated or developed from plants. Not necessarily a good idea.

The Doctrine of Signatures can make it fun to eat foods that are good for that also bear a resemblance to body organs. It’s probably not the best way to pick your medicines.

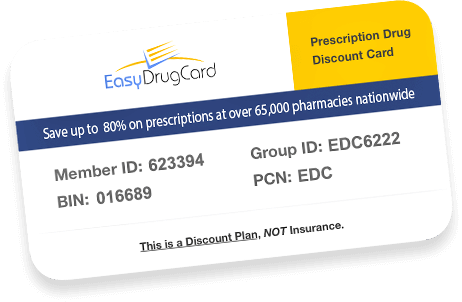

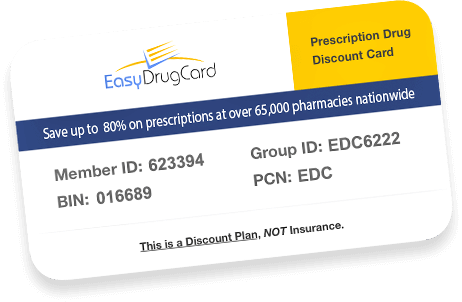

If you’re thinking of using a botanical, check with your prescriber or pharmacist. Certain botanicals can interact with medications, lab tests or disease states. Your community pharmacist should be able to check these out for you. And take good care of yourself.

Resources / References:

https://cannawellconsulting.files.wordpress.com/2014/10/doctrine-of-signatures.jpg