Testosterone – Good or Bad?

I believe that we absorb our world view during our youth, and carry that with us unchanged unless we make some effort to question our beliefs. My underlying assumptions about the pharmacology of sex steroids were recently challenged.

It will be fifty years ago this year that I graduated from St. James Grammar School in Red Bank, NJ. The world view of the Sisters of Mercy seemed pretty easy to understand at the time: boys are bad, girls are good. Yes, I had some colorful experiences.

Given my upbringing, it was natural for me to accept the idea that testosterone – a “boy” hormone – is bad for patients. Higher levels of testosterone are associated with aggression and crime. Testosterone levels are associated with acne.

It was only when my compounding pharmacist friend Sue asked me why I thought testosterone was bad that it came out: boy hormones are bad and girl hormones are good. Sue was able to see through this on two counts: she was educated in Iowa public schools, and she has seen testosterone help patients in her compounding pharmacy practice.

Just as women experience decreasing production of estrogen and progesterone as they age, men experience decreasing levels of testosterone as they get older. It’s estimated that a low testosterone level – “low T” – affects 20% of men age 60-70 and 50% of men over 80 years of age.

The big question has been whether lowering testosterone levels are good or bad.

The big question has been whether lowering testosterone levels are good or bad.

Low testosterone is judged based on the blood levels of testosterone and the absence or presence of low-T symptoms:

- decreased libido,

- erectile dysfunction,

- cognitive decline,

- depression,

- lethargy,

- osteoporosis,

- and decreased muscle mass and strength.

But low-T is also associated with an increase in all-cause mortality, coronary artery disease and stroke. So, men with low-T appear to feel worse and die sooner.

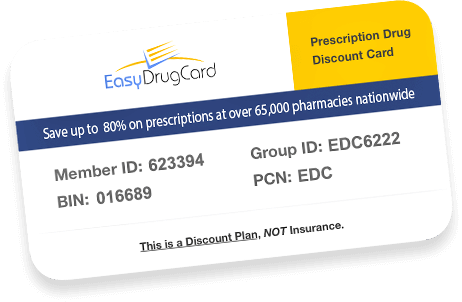

Testosterone can be supplemented through various dosage forms, including lozenges, injectable and topical formulations. Each dosage form has its own issues, but there have also been some issues raised concerning testosterone replacement in general.

Testosterone replacement therapy is associated with three major concerns and their potential impact on mortality. Polycythemia, an abnormal increase in the number of red blood cells and the thickness of the blood; this can produce a significant risk for cardiovascular disease. Testosterone can increase prostate size and there is concern about its influence on prostate cancer, although this has never been adequately studied. Testosterone also produces adverse lipid changes, such as a decrease in HDL, the good cholesterol.

A very small 2010 study of only about 100 patients showed an increase of cardiovascular events in patients receiving testosterone replacement. Meta analyses – statistical examinations of results from combinations of smaller studies – suggested an increase in cardiovascular risk in patients receiving testosterone replacement therapy.

In response, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the VA called for monitoring cardiovascular events in patients receiving testosterone replacement and reconsideration of the benefit:risk balance for testosterone. Enthusiasm for testosterone replacement was dampened, and you may have noticed that we’ve not seen a lot of “low-T” commercials over the last three years.

Meanwhile, advocates of testosterone replacement therapy note studies with opposite results: lower testosterone levels are associated with erectile dysfunction, atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease.

Some pharmacists, such as my friend Sue, note how much better their patients feel and do following testosterone replacement therapy.

A study published last month (Feb 13, 2017) in JAMA Internal Medicine examined the association of testosterone replacement therapy and cardiovascular disease outcomes in 8808 men with low-T who received testosterone compared to 35,000 men with low-T who had not received testosterone. This study found a significant decrease in mortality in low-T receiving testosterone.